Introduction

The complex and challenging pancreaticoduodenectomy,

sometimes called the “Whipple operation” is typically performed on elderly patients with pancreatic cancer and periampullary diseases. Younger patients are rarely given pancreaticoduodenectomy procedures, and the impact of age on surgical

and survival outcomes is still unclear [1].

Patients in their 30s or 40s are rarely found to have pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma, which is often detected in patients

aged 65-75 years of age [2,3]. The influence of youth on surgical

and survival outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy has

not been thoroughly investigated, given its uncommon occurrence in younger patients. There is little literature in this field

[1-5].

Traditionally, an open technique is used to perform pancreaticoduodenectomy using a high abdominal incision, right saber

slash, or a lengthy upper midline incision. This leads to severe

pain and sometimes even negative outcomes [6]. Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) has become the norm in several specialties, including pancreatic resection, because of reduced pain,

improved cosmesis, and smaller incisions. According to certain

findings, older people can have Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) with good results [7-9]. However, pancreaticoduodenectomy entails precise identification of the vital vascular anatomy, considerable dissection and removal of visceral

organs, and technically challenging repair. As a result, minimally

invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy is not as widely used [10].

Recently, robotic surgery has emerged to overcome the limitations of laparoscopic surgery, following the release of the Intelligent Surgical®, Sunnyvale, California, USA, da Vinci Robotic

Surgical Machine. This technology can offer tremor-free movements for both cams and tools, high-quality 3-Dimensional view

of the surgical field, and end wrist devices to enhance the spectrum of flexibility emulating open procedures.

These developments help lessen surgeon fatigue, enhance

ergonomics, and increase dexterity, but less used as its high

patients cost and less surgeon experiences [10,11]. Although

the robotic method of pancreaticoduodenectomy has been

adopted slowly, a number of studies have demonstrated that

RPD is a safe and viable technique compared with laparotomy

[6,10,12,13].

The majority of the information on surgical outcomes and

treatment choices that is currently accessible comes from studies conducted on older populations, as there is little research on

pancreaticoduodenectomy in younger individuals. Therefore, it

is unclear how younger and older groups differ in terms of tumor biology and surgical results. To date, there have we been

no studies on RPD in younger groups. To better understand the

clinicopathological characteristics, surgical outcomes, and survival outcomes of young patients (less than 50 years old) undergoing RPD, our study compared them with an older patient

cohort (>50 years old) undergoing RPD at our institute.

Patients and methods

Patient choice

The study comprised patients who underwent RPD at five

surgical institutes between Jan 2012 - Oct 2023 and data collected at our institute, 37 cases later, the learning curve for

the RPD was surmounted. The first RPD was completed on Jan.

2012.

Division of the patients into two categories based on the age,

RPD: young (less than 50 years) and old (>50 years). Any patient

had history of operation with marked adhesion >2 cm specially

upper part of the abdomen were excluded from our work.

Data gathering

All data related to patients character and tumor features

were collected, patients classified physically by the American

Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). All Preoperative , intraoperative and post operative morbidity were detected and gathered.

The likhookvarible associated with surgery, such as fatality and

different postoperative difficulties, were also evaluated. Periampullary adenocarcinoma death incidence have also been reported.

Aim of study outcomes

Primary aim of the study to contrast the safety and risks of

our cases categories. The secondary study goal is survival comparison between both.

Method procedures

A brief internal stent was inserted for a small pancreatic duct

measuring less than 3 mm, although pancreatic duct stents are

not commonly employed. The same jejunal limb was then used

for hepaticojejunostomy without stenting, either with continuous (for dilated) or interrupted (for non dilated ducts) sutures.

By carefully lowering the stomach, an extracorporeal technique

was used to execute hand-sewn gastrojejunostomy. The gastrojejunostomy was placed in framesocolic, antecolic, and antiperistaltic positions close to the umbilical region. When feasible, a restricted antrectomy was received following right gastric

artery bifercation in patients with an ischemic pylorus instead

of attempting pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Oral liquid after 24 h and soft diet after 3 days, no need for NGT

feeding.

The Clavien-Dindo classification was used to categorize surgical complications [14]. According to the 2016 International

Study Group for Pancreatic Fistula revised grading system [15],

clinically meaningful grade B or C pancreatic leakage constitutes

the definition of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (POPF). The

International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) established classification criteria for Delayed Gastric Emptying (DGE),

Post-Pancreatectomy Hemorrhage (PPH), and chyle leak [16-18].

Based on the state of the resection margin, compelete radical resection was we had three degree: If there was no microscopic evidence of cancer at a resection margin of less than 1

mm, the resection was classified as R0; if there was microscopic

evidence of cancer at a resection margin of less than 1 mm,

it was classified as R1; and if there was strong positive margin, it was classified as R2. Mortality that occurs through three

months following surgery, involving hospitalization period after

surgery, is referred to as surgical mortality.

Data statistics

The statistical product and service solutions version 26 program was used to perform the statistical analysis. Continuous

variables were compared using a two-tailed student’s t-test

and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The Wilcoxon

rank-sum test was used for continuous variables that were not

normally distributed. Categorical variables are represented as

numbers (percentages), and Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test contingency tables were used to compare them. The overall

survival between the young and old groups was compared using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and significance was assessed

using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression and

binary logistic regression were used for the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Table 1: Shows the demographics of the patients who underwent robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy with periampullary lesions.

|

Total |

Age <50 y/o |

Age ≥50 y/o |

P value |

| Patients, n(%) |

555 |

53(9.5%) |

502(90.5%) |

|

| Age, year old |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Median (range) |

67(13-97) |

42(13-49) |

68(50-97) |

|

| Mean±SDa |

66±12 |

40±9 |

69±9 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

0.512 |

| female |

259(46.7%) |

27(50.9%) |

232(46.2%) |

|

| male |

296(53.3%) |

26(49.1%) |

270(53.8%) |

|

| BMIb, kg/m2 |

|

|

|

0.628 |

| Median (range) |

23.5(15.4–36.2) |

23.1(16.7-34.1) |

23.5(15.4-36.2) |

|

| Mean±SD |

23.7±3.5 |

23.9±4.1 |

23.7±3.4 |

|

| ASAc physical status classification |

|

|

<0.001 |

| <3 |

359(64.7%) |

48(90.6%) |

311(62.0%) |

|

| ≥3 |

196(35.3%) |

5(9.4%) |

191(38.0%) |

|

| Periampullary lesions |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Pancreatic head adenocarcinoma |

193(34.8%) |

7(13.2%) |

186(37.1%) |

|

| Ampullary adenocarcinoma |

139(25.0%) |

6(11.3%) |

133(25.5%) |

|

| Distal CBDdadenocarcinoma |

43(7.7%) |

0(0.0%) |

43(8.6%) |

|

| Duodenal adenocarcinoma |

26(4.7%) |

4(7.5%) |

22(4.4%) |

|

| IPMNe |

43(7.7%) |

4(7.5%) |

39(7.8%) |

|

| Neuroendocrine tumor |

26(4.7%) |

8(15.1%) |

18(3.6%) |

|

| Solid and pseudopapillary tumor |

10(1.8%) |

5(9.4%) |

5(1.0%) |

|

| Chronic pancreatitis |

16(2.9%) |

5(9.4%) |

11(2.2%) |

|

| Other malignant tumor |

33(5.9%) |

7(13.2%) |

26(5.2%) |

|

| Other benign tumor |

26 (4.7%) |

7(13.2%) |

19(3.8%) |

|

| Periampullary adenocarcinomas |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Yes |

401(72.3%) |

17(32.1%) |

384(76.5%) |

|

| No |

154(27.7%) |

36(57.9%) |

118(23.5%) |

|

| Periampullary adenocarcinomas |

|

|

0.626 |

| Pancreatic head adenocarcinomas |

193(48.1%) |

7(41.2%) |

186(48.4%) |

|

| Other periampullary adenocarcinoma |

208(51.9%) |

10(58.8%) |

198(51.6%) |

|

| Pancreatic parenchyma |

|

|

|

0.033 |

| soft |

355(64.0%) |

41(77.4%) |

314(62.5%) |

|

| hard |

200(36.0%) |

12(22.6%) |

188(37.5%) |

|

| Pancreatic duct |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| non-dilated ≤3 mm |

270(49.3%) |

41(77.4%) |

229(46.3%) |

|

| dilated >3 mm |

278(50.7%) |

12(22.6%) |

266(53.7%) |

|

| Tumor size, cm |

|

|

|

0.263 |

| Median (range) |

3.0(0.5-11.0) |

3.0(1.0-8.5) |

3.0(0.5-11.0) |

|

| Mean±SD |

3.1±1.4 |

3.3±1.7 |

3.1±1.4 |

|

aSD: standard deviation; bBMI: body mass index; cASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; dCBD: common bile duct; eIPMN: intraductal papillary

mucinous neoplasm

Results

This study included 555 patients; 53(9.5%) belonged to

the younger group (age <50 years), whereas 502(90.5%) belonged to the older group (age ≥50 years) (Table 1). Regarding

the demographics of the two groups, there were no notable

differences in terms of sex, BMI, or tumor size. Nonetheless,

a greater percentage of patients in the younger cohort were

classified as having an ASA physical status ≥3 (9.4% vs. 38.0%,

p<0.001). Periampullary adenocarcinomas were less common

in the younger group than in the older group (32.1% vs 76.5%,

p<0.001). However, solid and pseudopapillary tumors (9.4% vs.

1.0%) and neuroendocrine tumors (15.1% vs. 3.6%) were more

common in the younger patients. Two types of periampullary

adenocarcinoma were found in the same number of young and

old people (p=0.626): Periampullary adenocarcinoma in the

pancreatic head (41.2% vs. 48.4%) and other types (58.8% vs.

51.6%). Some pancreatic ducts were not dilated (≤3 mm) more

often in the younger group (77.4% vs. 46.3%, p < 0.001), and the

pancreatic parenchyma was softer (77.4% vs. 62.5%, p=0.033).

In terms of surgical outcomes (Table 2), there were no statistically significant differences between the young and old groups

in terms of operation time (median, 7.8 vs. 8.3 h; p=0.508), intraoperative blood loss (median, 100 vs. 160 mL; p=0.681), surgical radicality (R0 resection, 92.5% vs. 85.1%; p=0.217), lymph

node yield (median, 17 vs. 18; p=0.681), lymph node involvement (50.0% vs. 56.1%, p=0.798), stage 1 + 2 (58.8% vs. 70.6%, p = 0.292), conversion rate (5.7 vs. 8.4%, p = 0.492), and vascular

resection rate (3.8% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.997). In the younger group,

the majority of the surgical outcomes were positive. Compared

to the senior group (median of 20 days), the LOS of the young

group was shorter (median of 16 days; p = 0.033). Age by itself

was not an independent predictor of longer length of stay (LOS)

following RPD, although pancreatic head adenocarcinoma (+),

morbidity (+), POPF (+), and chyle leakage (+) were observed on

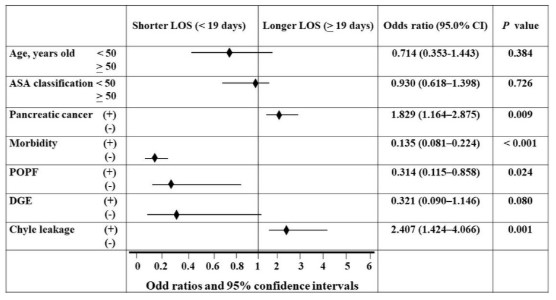

multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression (Figure 1).

The Length of Stay (LOS) following robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy was predicted by the independent components, as

shown in Figure 1’s forest plot of multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression. US Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA);

Reliability interval (CI); Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (POPF);

Delayed Gastric Emptying (DGE).

Table 2: Surgical results following pancreaticoduodenectomy using robotics.

|

Total |

Age <50 y/o |

Age ≥50 y/o |

P value |

| Patients, n |

555 |

53(9.5%) |

502(90.5%) |

|

| Operation time, hour |

|

|

|

0.508 |

| Median (range) |

8.0(3.3-16.3) |

7.8(4.0-13.5) |

8.3(3.3-16.3) |

|

| Mean±SDa |

8.4±2.3 |

7.9±2.3 |

8.4±2.3 |

|

| Blood loss, c.c. |

|

|

|

0.681 |

| Median (range) |

160(0-6000) |

100(0-4600) |

160(0-6000) |

|

| Mean±SD |

239±396 |

261±666 |

237±357 |

|

| Surgical radicality |

|

|

|

0.217 |

| R0 |

476(85.8%) |

49(92.5%) |

427(85.1%) |

|

| R1 |

57(10.3%) |

4(7.5%) |

53(10.6%) |

|

| R2 |

22(4.0%) |

0 |

22(4.4%) |

|

| Lymph node yield |

|

|

|

0.351 |

| Median (range) |

18(12-49) |

17(12-37) |

18(12-49) |

|

| Mean±SD |

19±6 |

18±6 |

19±5 |

|

| Lymph node involvement |

218(55.9%) |

8(50.0%) |

210(56.1%) |

0.798 |

| Stage |

|

|

|

0.292 |

| 1+2 |

281(70.1% |

10(58.8%) |

271(70.6%) |

|

| 3+4 |

120(29.9%) |

7(41.2%) |

113(29.4%) |

|

| Conversion to open, n (%) |

45(8.1%) |

3(5.7%) |

42(8.4%) |

0.492 |

| Vascular resection, n (%) |

21(3.8%) |

2(3.8%) |

19(3.8%) |

0.997 |

| LOSb, day |

|

|

|

0.033 |

| Median (range) |

19(6-118) |

16(6-46) |

20(6-118) |

|

| Mean±SD |

23±14 |

19±9 |

23±14 |

|

aSD: standard deviation; bLOS: length of stay

Table 3: Risks associated with surgery following robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy

|

Total |

Age <50 y/o |

Age ≥50 y/o |

P value |

| Patients, n |

555 |

53(9.5%) |

502(90.5%) |

|

| Surgical mortality |

8(1.5%) |

0 |

8(1.6%) |

0.352 |

| Surgical morbidity |

312(56.2%) |

28(52.8%) |

284(56.6%) |

0.601 |

| Surgical complication |

|

|

|

0.888 |

| Clavien–Dindo 0 |

236(42.5%) |

23(43.4%) |

213(42.4%) |

|

| Clavien–Dindo I |

191(34.4%) |

18(34.0%) |

173(34.5%) |

|

| Clavien–Dindo II |

52(9.4%) |

5(9.4%) |

47(9.4%) |

|

| Clavien–Dindo III |

62(11.2%) |

7(13.2%) |

55(11.0%) |

|

| Clavien–Dindo IV |

5(0.9%) |

0 |

5(1.0%) |

|

| Clavien–Dindo V (death) |

9(1.6%) |

0 |

9(1.8%) |

|

| Severity of complication, n=319 |

|

|

|

0.947 |

| Minor (Clavien–Dindo I-II) |

243(76.2%) |

23(76.7%) |

220(76.1%) |

|

| Major (Clavien–Dindo≥III) |

76(23.8%) |

7(23.3%) |

69(23.9%) |

|

| POPFa (ISGPFb grade B and C) |

| Overall |

44(7.9%) |

4(7.5%) |

40(8.0%) |

0.914 |

| Parenchyma of pancreas |

| soft |

37(10.4%) |

4(9.8%) |

33(10.5%) |

0.882 |

| hard |

7(3.5%) |

0 |

7(3.7%) |

0.496 |

| Diameter of pancreatic duct |

| non-dilated ≤3 mm |

30(11.1%) |

4(9.8%) |

26(11.4%) |

0.746 |

| dilated >3 mm |

14(5.0%) |

0 |

14(5.3%) |

0.415 |

| DGEc (ISGPSd grade B and C) |

24(4.3%) |

1(1.9%) |

23(4.6%) |

0.359 |

| PPHe (ISGPSd grade B and C) |

32(5.8%) |

4(7.5%) |

28(5.6%) |

0.559 |

| Chyle leakage |

140(25.2%) |

14(26.4%) |

126(25.1%) |

0.834 |

| Bile leakage |

10(1.8%) |

1(1.9%) |

9(1.8%) |

0.961 |

| Wound infection |

28(5.0%) |

1(1.9%) |

27(5.4%) |

0.269 |

aPOPF: Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula, bISGPF: International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula; cDGE: Delayed Gastric Emptying; dISGPS: International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery; ePPH: Postpancreatectomy Hemorrhage.

With no surgical mortality in the young group and 1.6% in

the old group (p=0.352), the cohort’s overall surgical mortality

rate was 1.5%. All patients had a DGE rate of 4.3%:1.9% in the

young group and 4.6% in the old group (P=0.359). With 7.5% in

the young group and 8.0% in the old group, the overall POPF

rate was 7.9% (P=0.914). Additionally, there were no appreciable differences between the younger and older groups in terms

of surgical morbidity, Clavien-Dindo surgical complications, severity of problems, PPH, chyle leakage, bile leakage, or wound

infection (Table 3).

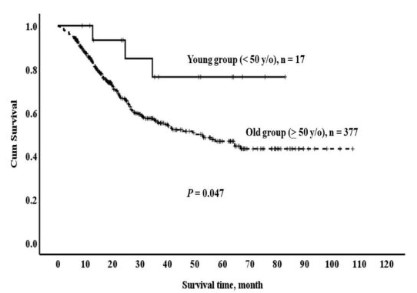

Regarding survival results, 48.1% of the total cohort with

periampullary adenocarcinomas survived for five years (Table

4). In terms of overall periampullary adenocarcinoma, the

5-year survival rate of the younger group was considerably

higher than that of the older group (76.4% vs. 46.7%, p=0.047)

(Figure 2). The 5-year survival rates for ampullary adenocarcinoma and pancreatic head adenocarcinoma were 100% vs. 61.4%

(p=0.159) and 62.5% vs. 31.4% (p=0.171), respectively. However, there was no clear difference between the two groups in

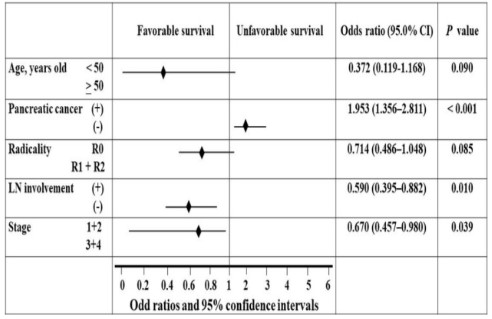

terms of survival rates. The Cox proportional hazards regression

model (Figure 3) showed that age was not a reliable predictor

of poor survival after robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. However, pancreatic head cancer (+), Lymph Node (LN) involvement

(+), and late stage 3+4 (+) were observed.

To estimate how long someone will live after a robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy, we used the Cox proportional hazards

regression model and the forest plot in Figure 3 to identify independent prognostic factors.

Table 4: Survival rates following robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinomas.

| Periampullary adenocarcinoma |

Median, (mon.) |

Range, (mon.) |

Mean ± SDa, (mon.) |

1-year survival |

3-year survival |

5-year survival |

P value |

| Overall periampullary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total, n=394 |

20.4 |

0.2-107.6 |

28.7+23.3 |

85.4% |

57.1% |

48.1% |

0.047 |

| Age <50 y/o, n=17 |

35.3 |

8.9-82.9 |

40.1±24.2 |

100% |

76.4% |

76.4% |

|

| Age ≥50 y/o, n=377 |

20.2 |

0.2-107.6 |

28.2±23.2 |

84.7% |

56.2% |

46.7% |

|

| Pancreatic head |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total, n=191 |

16.6 |

0.8-98.1 |

23.0±19.8 |

77.8% |

40.4% |

32.9% |

0.171 |

| Age <50 y/o, n=7 |

24.6 |

8.9-67.3 |

34.4±22.4 |

100% |

62.5% |

62.5% |

|

| Age ≥50 y/o, n=184 |

16.5 |

0.8-98.1 |

22.6±19.6 |

76.9% |

39.4% |

31.4% |

|

| Ampullary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total, n=136 |

28.1 |

0.2-107.6 |

35.7±26.3 |

91.3% |

73.9% |

63.1% |

0.159 |

| Age <50 y/o, n=6 |

43.4 |

11.7-75.6 |

41.9±29.0 |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

| Age ≥50 y/o, n=130 |

28.1 |

0.2-107.6 |

35.7±26.3 |

90.9% |

72.8% |

61.4% |

|

aSD: standard deviation.

Discussion

Given that less than 30% of tumors are projected to arise in

young people, pancreatic cancer and other periampullary malignancies are uncommon among younger patients compared

to older patients [19]. This is particularly true for pancreatic

cancer and other periampullary malignancies. Malignancies in

young people may differ from those in the elderly in terms of

their molecular characteristics and tumor biology. Although

there is debate about whether young patients have a worse

prognosis than older patients, our present understanding of

cancer in this population is inadequate [2]. Furthermore, the

implementation of MIS occurs more frequently. Nevertheless,

little research has been conducted on how early age affects surgery and survival after RPD.

Periampullary adenocarcinomas were less common in the

younger group (32.1% vs. 76.5%) than in the older group. In

contrast, the younger group had higher rates of solid and pseudopapillary tumors (9.4% vs. 1.0%) and neuroendocrine tumors

(15.1% vs. 3.6%). In a study of pancreaticoduodenectomy in a

young population (≤30 years old), Mansfield et al. [20] discovered that chronic pancreatitis (6, 27.3%) was the most common

postoperative histologic diagnosis, followed by solid pseudopapillary tumors (22.7%) and adenocarcinomas (18.2%). A case

series of young adults (less than 35 years) who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy was described by El Nakeeb et al. [1].

The results showed that adenocarcinoma (41.4%) was the most

common pathological diagnosis in this cohort, followed by solid

pseudopapillary tumors (29.3%). Although the most common diagnosis reported in the literature is inconsistent, solid pseudopapillary tumors have become a common histological diagnosis in young individuals.

Younger people may be more susceptible to pancreatic leakage because they often have a smaller pancreatic duct, a less

fibrotic pancreas, and a more normal pancreatic parenchyma.

As predicted, the prevalence of non-dilated (<3 mm) pancreatic

ducts and soft pancreatic parenchyma was higher in the younger group (77.4% vs. 62.5% and 77.4% vs. 46.3%, respectively).

Despite these variations, the younger group did not have an

increase in POPF or surgical complications compared with the

older group. Furthermore, there was no surgical mortality in the

younger group, supporting the findings of other studies [1,5,20]

that RPD are safe for young patients. Although the youth group

in this study had a shorter LOS (median: 16 vs. 20 days), age by

itself was not an independent predictor of LOS following multivariate analysis. Most likely, reduced morbidity, lower POPF,

and fewer cases of pancreatic head adenocarcinoma contributed to the shorter LOS in younger patients.

There is ongoing discussion regarding the relative aggressiveness of younger versus older patients with pancreatic duct

adenocarcinomas [2-5]. Meng et al. [5] found no significant correlation between age and long-term survival in patients with

pancreatic and periampullary adenocarcinomas after LPD. Additionally, Yeh et al. [21] showed that, following pancreaticoduodenectomy, actuarial survival was comparable between older

and younger patients. According to several experts, cancer in

older adults might be less aggressive biologically [22,23]. Consequently, it is believed that younger cancer patients have a

poorer prognosis than older ones [24-27]. After radical resection

of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Tang et al. [2] compared

adolescents and young adults using propensity score matching and concluded that the disease may be more aggressive in

these age groups. Additionally, Mansfield et al. [20] found that

the median survival for juvenile adenocarcinoma patients was

10.2 months, compared to 57.8 months for adult patients. However, El Nakeeb et al. [1] demonstrated that the median survival of young adult patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma

was much better than that of older patients, in contrast to the

findings of Tang and Mansfield [2,20]. In this investigation, the

younger group outperformed the older group by five years for

total periampullary adenocarcinoma (76.4% vs. 46.7%). In both the ampullary and pancreatic head adenocarcinoma groups,

there was a trend toward improved survival outcomes in the

younger group, although the difference was not statistically significant. Age was not an independent predictive factor for periampullary adenocarcinoma after multivariate analysis. This may

be because our study included fewer cases of pancreatic head

cancer and lymph node involvement. Nevertheless, the small

sample size of the young group made it difficult to reach firm

conclusions. Larger sample sizes and additional research are required to validate these results and to explore the underlying

mechanisms.

This study had certain shortcomings. Initially, all adult patients were included in the older cohort regardless of their

comorbidities or overall health. Second, the small sample size

of the young group makes statistical errors more likely and restricts our ability to properly grasp biological aggression.

Conclusions

Individuals under 50 years of age can safely undergo RPD,

and their surgical results will be similar to those of older individuals. Additionally, although the results were not independent,

younger patients with periampullary adenocarcinoma showed

considerably better survival outcomes than older patients.

These results lend credence to the viability and possible advantages of RPD in the pediatric population. Further investigation

with a larger sample size is required to verify these results and

to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Declarations

Acknowledgment: Not applicable.

Declaration and ethical clearance: Ethical clearance was

obtained from Zagagic University, Faculty of Medicine, Institutional Health Research Ethics (IHRERC), and written informed

consent was obtained from the Review IHRERC under No. (ethical protocol number ZU-IRB#99902792023). Written informed

consent was obtained from the Zagazig University Hospital database in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials: A database is available to

the corresponding author. This database is available upon review and request. All authors shared the database.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no

competing interests or financial disclosures.

Funding: No specific funds were received for this study

References

- El Nakeeb A, El Sorogy M, Salem A, Said R, El Dosoky M, et al.

Surgical outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy in young patients: A case series. Int J Surg. 2017; 44: 287-294.

- Tang N, Dou X, You X, Liu G, Ou Z, et al. Comparisons of Outcomes Between Adolescent and Young Adult with Older Patients

After Radical Resection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by

Propensity Score Matching: A Single-Center Study. Cancer Manag Res. 2021; 13: 9063-9072.

- Barbas AS, Turley RS, Ceppa EP, Reddy SK, Blazer DG, et al. Comparison of outcomes and the use of multimodality therapy in

young and elderly people undergoing surgical resection of pancreatic cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012; 60: 344-350.

- Liu Q, Zhao Z, Zhang X, Zhao G, Tan X, et al. Robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly and younger patients: A retrospective

cohort study. Int J Surg. 2020; 81: 61-65.

- Meng L, Xia Q, Cai Y, Wang X, Li Y, et al. Impact of Patient Age

on Morbidity and Survival Following Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019; 29:

378-382.

- Shyr BU, Shyr BS, Chen SC, Shyr YM, Wang SE. Mesopancreas

level 3 dissection in robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery.

2021; 169: 362-368.

- Kim JS, Choi M, Kim SH, Choi SH, Kang CM. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in octogenarians.

Asian J Surg. 2022; 45: 837-843.

- Chapman BC, Gajdos C, Hosokawa P, Henderson W, Paniccia A,

et al. Comparison of laparoscopic to open pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Surg Endosc. 2018; 32: 2239-2248.

- Jones LR, Zwart MJW, Molenaar IQ, Koerkamp BG, Hogg ME, et

al. Robotic Pancreatoduodenectomy: Patient Selection, Volume

Criteria, and Training Programs. Scand J Surg. 2020; 109: 29-33.

- Mantzavinou A, Uppara M, Chan J, Patel B. Robotic versus open

pancreaticoduodenectomy, comparing therapeutic indexes; a

systematic review. Int J Surg. 2022; 101: 106633.

- van Oosten AF, Ding D, Habib JR, Irfan A, Schmocker RK, et al.

Perioperative Outcomes of Robotic Pancreaticoduodenectomy:

A Propensity-Matched Analysis to Open and Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021; 25: 1795-

1804.

- Shyr BU, Chen SC, Shyr YM, Wang SE. Surgical, survival, and oncological outcomes after vascular resection in robotic and open

pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2020; 34: 377-383.

- Wang SE, Shyr BU, Chen SC, Shyr YM. Comparison between

robotic and open pancreaticoduodenectomy with modified

Blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy: A propensity score-matched

study. Surgery. 2018; 164: 1162-1167.

- Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, et al.

The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009; 250: 187-196.

- Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, et al.

The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years

After. Surgery. 2017; 161: 584-591.

- Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al.

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: A suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic

Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007; 142: 761-768.

- Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, et al. Post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): An International Study

Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;

142: 20-25.

- Besselink MG, van Rijssen LB, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Montorsi M,

et al. Definition and classification of chyle leak after pancreatic

operation: A consensus statement by the International Study

Group on Pancreatic Surgery. Surgery. 2017; 161: 365-372.

- Langan RC, Huang CC, Mao WR, Harris K, Chapman W, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy hospital resource utilization in octoge-

narians. Am J Surg. 2016; 211: 70-75.

- Mansfield SA, Mahida JB, Dillhoff M, Porter K, Conwell D, et al.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy outcomes in the pediatric, adolescent, and young adult population. J Surg Res. 2016; 204: 232-

236.

- Yeh CC, Jeng YM, Ho CM, Hu RH, Chang HP, et al. Survival after

pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary cancer is not affected

by age. World J Surg. 2010; 34: 2945-2952.

- Fisher CJ, Egan MK, Smith P, Wicks K, Millis RR, et al. Histopathology of breast cancer in relation to age. Br J Cancer. 1997; 75:

593-596.

- Monson K, Litvak DA, Bold RJ. Surgery in the aged population:

surgical oncology. Arch Surg. 2003; 138: 1061-1067.

- Cho SJ, Yoon JH, Hwang SS, Lee HS. Do young hepatocellular carcinoma patients with relatively good liver function have poorer

outcomes than elderly patients? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;

22: 1226-1231.

- Emile SH, Elfeki H, Shalaby M, Elbalka S, Metwally IH, et al. Patients with early-onset rectal cancer aged 40 year or less have

similar oncologic outcomes to older patients despite presenting

in more advanced stage; A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg.

2020; 83: 161-168.

- Llanos O, Butte JM, Crovari F, Duarte I, Guzmán S. Survival of

young patients after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J

Surg. 2006; 30: 17-20.

- Nakamura R, Saikawa Y, Takahashi T, Takeuchi H, Asanuma H, et

al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic outcome of gastric cancer in young patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011; 16: 328-334.