Introduction

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) is defined as accumulation of air in the pleural space in patients without a history of underlying lung disease [1]. Varying hypotheses exist as

to why it occurs, including spontaneous rupture of blebs [2], the

impact of greater distending pressures to the lung apex during

growth spurts, or pleural porosity [3,4]. PSP is most prevalent in

thin adolescent males [5] who typically present with acute onset unilateral chest pain and less frequently dyspnea and cough

[6].

While PSP is a well-defined pathology in pediatrics, there is

marked variability in management strategies, including rate and

route of oxygen administration [7], use of suction [8], and placement of small versus large bore tube thoracostomies [9,10]. A

recent survey of North American Surgeons demonstrated significant variability in the management of PSP [10]. Approximately 78% of pediatric patients with PSP undergo intervention

[3,5,6,11-14]; however recent literature questions the need for

interventional management. In 2020, Brown et al. published

an open-label, multi-center non-inferiority trial of 316 patients

14-50 years of age with PSP, demonstrating that conservative

management (analgesia and oxygen use) was non-inferior to

placement of a small-bore chest tube when evaluating lung reexpansion within 8 weeks [15]. Furthermore, patients with conservative management experienced fewer hospitalized days,

fewer adverse events and a lower likelihood of recurrence [15].

A recent meta-analysis supports conservative management by

demonstrating equivocal risk of PSP recurrence when comparing conservative management to tube thoracostomy. A lower

risk of adverse events was demonstrated in the conservative

management group with no difference noted in the rate of PSP

resolution [16].

Brown et al. provides strong evidence that conservative

management is safe in the adult population, but the median

age was 26 years old with a standard deviation of 8 raising concern for how this extrapolates to a pediatric population [15].

Our first aim was thus to determine the safety of translating

the recommendations surrounding conservative management to the pediatric population [15]. We also hoped to fill

the gap of primary literature focusing solely on the pediatric

population [17]. There have been no recent pediatric studies

evaluating current practice surrounding PSP and establishing

baseline data prior to transition to conservative management.

Specifically, the last case series of pediatric PSP were published

in 2015 from Australia [5] and the United Kingdom [11], prior

to the new evidence on conservative management. Given this

gap surrounding management of pediatric patients, significant

management variation and emerging data of non-inferiority of

conservative management, we sought to describe the characteristics and outcomes of patients with PSP presenting to our

pediatric emergency department (ED) from 2014-2021.

Methods

Study setting and design

We conducted a descriptive study of pediatric patients diagnosed with primary spontaneous pneumothorax who presented to the ED from 2014 to 2021. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Medical Center (CCHMC) is a 600-bed quaternary care pediatric referral center with EDs in two freestanding children’s hospitals,

one urban and the other suburban. The hospital has approximately 100,000 emergency department (ED) visits and 20,000

admissions annually. The ED is staffed by pediatric and emergency medicine residents supervised by pediatric emergency

medicine fellows and attendings. Additionally, clinical staff

(nurse practitioners and pediatricians) see patients independently. Our institutional review board approved the study prior

to commencement and granted waiver of informed consent

(IRB ID 2021-0553).

Sample description and data collection

All children less than 21 years of age who presented for care

to either ED were eligible for inclusion. Eligible patients were

identified using International Classification of Diseases, 10th

revision (ICD-10) codes for pneumothorax (93.9,93.11,93.83,

95,811,93.12,93.0). A detailed electronic medical record (EMR)

review was performed to identify patients with a first-time episode of x-ray confirmed pneumothorax as read by a pediatric

radiologist. Secondary pneumothorax, including trauma, pre-disposing underlying lung disease and infection were excluded.

Underlying lung disease was defined as any lung condition that

predisposed to pneumothorax, including asthma, congenital

diaphragmatic hernia, tuberous sclerosis. Additionally, patients

were excluded if the pneumothorax developed while inpatient

or management was performed at an outside facility.

Data were collected through manual chart review. Variables

extracted from the electronic medical record included patient

age, sex, triage vital signs, and disposition. We subcategorized

age less than 10 as the incidence of PSP is known to be very

low in this age group. Chief complaint was extracted from the

provider note. We utilized the initial chest x-ray (CXR) to determine pneumothorax laterality. Determination of pneumothorax

size was at the discretion of the radiologist, either subjective

or using objective measurements [18-20]. We defined small

pneumothorax as a radiologist reading of tiny, trace, small,

small to moderate or moderate pneumothorax. Large pneumothorax was defined as moderate to large or large according to

radiologist read. Hypoxia was defined as an oxygen saturation

less than 90% on room air. Oxygen use was defined as receipt

of any amount of oxygen via nasal cannula, oxymask or non-rebreather. Patients were deemed to have tension physiology

if they had hypotension associated with tachycardia [21]. The

tube thoracostomy procedure note was reviewed for catheter

size, use of anxiolytics or analgesics, and primary proceduralist.

Small bore chest tube was defined as <14 French [22]. Length

of stay (LOS) was calculated from time of hospital admission to

time of discharge as noted in the encounter timeline. All imaging and procedure notes were reviewed to establish if computed tomography (CT) or video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS)

occurred during the initial encounter. All subsequent encounters were reviewed for recurrence defined as any future occurrence of pneumothorax on CXR after a CXR demonstrated complete resolution of initial pneumothorax. Patients were marked

as having a follow-up CXR if an x-ray was performed at CCHMC

within 8 weeks of initial presentation [15].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (counts and percentages) were used to summarize patient characteristics and management strategies. Continuous variables were described using means and

range. All analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel.

Results

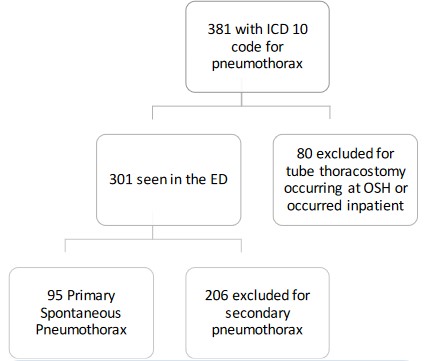

A total of 381 patients were evaluated for eligibility, 95 of

which had PSP and were included in the analyses (Figure 1). Two

hundred and six patients were excluded for secondary pneumothoraces: 94 had recurrent disease, 9 developed a pneumothorax in the setting of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 17 had

an associated pleural effusion, 37 had traumatic processes, 30

had an underlying lung disease, and 19 had a lower respiratory

tract infection at the time of pneumothorax. Table 1 displays

the characteristics of the study sample.

Chief complaint consisted of chest pain (n=79, 83%), dyspnea

(n=4, 4%), shoulder, arm or back pain (n=6, 6%), cough (n=2,

2%), foreign body sensation (n=1, 1%), chest palpitations (n=1,

1%), abdominal pain (n=1, 1%) and incidental pneumothorax

found on x-ray of spine (n=1, 1%). None of the patients in the

study sample were hypoxic, but 86% received oxygen therapy.

Seven patients were discharged home after observation in the

ED. The remainder were admitted to pediatric surgery (n=76,

80%), hospital medicine (n=8, 8%), pulmonology (n=2, 2%), or

hematology (n=1, 1%) services. One patient required admission

to the pediatric intensive care unit for sedation in the setting

of significant anxiety. Thirty-eight chest tubes were placed in

the ED; 17 by ED providers and 21 by surgery providers. Ninetyfive percent (n=18) of patients with large pneumothorax had

tube thoracostomy compared to 39% (n=27) of those with small

pneumothorax. No patients had tension physiology. One patient was admitted with a plan for interventional radiology (IR)

to perform a tube thoracostomy. Nine patients were initially admitted for observation but due to enlarging or unchanged pneumothorax on repeat CXR, tube thoracostomy was performed by

IR. Time between initial CXR and the CXR that prompted tube

thoracostomy ranged from 6 to 39 hours. All chest tubes placed

by IR required general anesthesia, while the ED used ketamine

(n=29, 76%), opiates (n=8, 21%), or midazolam (n=1, 3%). In the

48 patients who had a chest tube placed, 31(65%) had documented administration of local analgesia. Forty-six patients with

tube thoracostomy received low wall suction. During the course

of treatment, including follow-up x-rays, patients received on

average 6.4 CXRs.

Overall, recurrence rate was 31% (n=29), 38 % in those who

underwent tube thoracostomy and 23% in those who did not.

After discharge from the hospital (n=14) or the ED (n=1), 15

(16%) patients returned to the ED within 8 weeks for pneumothorax related complaints. Return reasons included recurrence

after full resolution noted on CXR (n=9), chest pain/costochondritis (n=1), post-surgical pain (n=1), enlarging pneumothorax requiring admission for observation (n=1), and enlarging

pneumothorax warranting chest tube placement (n=3). Of the

4 patients who returned for enlarging pneumothorax, none

had concern for tension physiology at time of re-presentation.

Twenty patients had a PSP recurrence 9 weeks or greater from

initial PSP. Timing of recurrence ranged from 9 weeks to 2 years.

Management of recurrent PSP was variable with 7 patients

(35%) undergoing conservative management, 1 patient (5%)

undergoing tube thoracostomy, 11 patients (55%) having VATS,

and 1 patient’s (5%) management was unknown as treatment

occurred outside of our institution.

Table 1: Summary characteristics of patients with first encounter for PSP (N=95).

| Patient Characteristics |

N (%) |

| Presentation |

|

| Age in years (mean, range) |

16.3, 8-20 |

| Age less than 10 years |

1 (1) |

| Male |

83 (87) |

| Pneumothorax laterality on CXR |

|

| Right |

30 (32) |

| Left |

61 (64) |

| Bilateral |

4 (4) |

| Pneumothorax size |

|

| Small |

69 (73) |

| Large |

19 (20) |

| No size description |

7 (7) |

| Triage Vitals (mean, range) |

|

| Heart rate |

89, 51-150 |

| Respiratory rate |

20, 10-36 |

| Pulse oximetry |

99, 92-100 |

| Systolic blood pressure |

125, 89-175 |

| Diastolic blood pressure |

75, 43-106 |

| Management |

|

| Received oxygen |

82 (86) |

| Tube thoracostomy |

48 (50) |

| Small bore |

33 (69) |

| Large bore |

14 (29) |

| Size not documented |

1 (2) |

| Discharged home from ED |

7 (7) |

| Admitted |

|

| Admitted after tube thoracostomyor planned |

39 (44) |

| placement |

|

| Admitted for observation |

40 (45) |

| Converted from observation to tubethoracostomy |

9 (10) |

| Length of stay for admission (meanhours, range) |

|

| Tube thoracostomy |

118, 12-407 |

| No tube thoracostomy |

16.7, 7-32 |

| Chest computed tomography scan |

19 (20) |

| VATS |

22 (23) |

| Follow-up |

|

| Patients with 1 recurrence |

29 (31) |

| Follow-up x-ray in 8 weeks |

71 (75) |

*CXR:chest x-rays; VATS: video assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Discussion

Our retrospective case series of 95 pediatric patients with PSP

is the largest in the United States and provides several insights

into the presentation, management and outcomes of patients

evaluated in our pediatric EDs. The predominantly adolescent

male population and recurrence rate observed are consistent

with prior published studies [5,23]. As predicted, there was significant variation in the management of PSP regarding oxygen

administration, procedural intervention, and disposition with a

resultant wide range in mean LOS. Most notably, no patients

developed tension physiology.

Patients with PSP are frequently placed on oxygen due to

a theoretical nitrogen washout leading to an increased rate of

resolution, which was initially proposed in 1932 [24] and further explained by an animal model in 1995 [25]. Evidence on

the effect of oxygen administration on rate of resorption and

how it relates to pneumothorax size is contradicting, with some

proposing a greater effect on small pneumothoraces [26] and

others postulating that effect on large pneumothoraces [27].

Park et al. retrospectively reviewed PSP cases to evaluate rate

of resorption on room air vs oxygen [7]. They found a minimally

increased rate of resolution with oxygen administration, but

these finding were confounded by a selection bias as patients

with large pneumothoraces received oxygen while those with

small pneumothoraces were managed outpatient. There have

been no prospective studies to evaluate indications for oxygen

therapy in PSP and no standardized recommendations for route

or fraction of inspired oxygen to administer. Thus as expected,

while most patients in our study were placed on oxygen, the

route and fraction of inspired oxygen was inconsistent ranging

from nasal cannula to 15 liters per minute via non-rebreather.

The initiation and discontinuation criteria for oxygen administration were unclear, which is note-worthy given the lack of hypoxia in our patient population.

It is also important to note in our study, only a minority admitted for observation eventually required tube thoracostomy

and that none of these patients developed tension physiology

after deferring initial tube thoracostomy. No patients returning to the ED with post-discharge enlarging pneumothorax

developed tension physiology. We speculate that the fear of

development of tension physiology likely impacts clinician decision to perform tube thoracostomy. Recent evidence indicates

that development of tension physiology is extremely rare in

PSP and potentially not physiologically possible in a spontaneously breathing patient due to an inability for the pressure in

the pneumothorax to exceed 1 standard atmospheric unit [28].

Combined, these findings support the consideration of observational management in the pediatric population [15,16].

Leading societies disagree on the preferred method for

pneumothorax size calculation. The British Thoracic Society

(BTS), American College of Chest Physicians, and the Belgian

Society of Pulmonology all utilize unique definitions of small

versus large pneumothorax that rely on single measurements

from CXR [18,19]. The Collin’s formula is an additional measurement strategy that requires 3 measurements but it is has only

been studied in a small sample of adults and not yet validated

[20]. The BTS calculation differentiates small versus large pneumothorax based on less than or greater than 2 cm from chest

wall to lung margin. No standardized measurement strategy has

been developed for the pediatric population, as varying chest

size in a growing child limits its feasibility. Pneumothorax size

calculations in our study were at the discretion of the radiologist and no uniform calculations were used. Pneumothorax size

is a significant factor in management decisions thus we hypothesize this led to variability in decision to pursue tube thoracostomy. The subjective nature of pneumothorax size is a major

barrier to standardizing PSP care and a vital gap in literature

highlighted by our case series.

Amongst the patients who received tube thoracostomy,

catheter size, use of local analgesia and suction, and decisions

leading to disposition were not uniform. Variability surrounding catheter size and the use of large bore catheters leads to

increased patient discomfort without benefit as larger catheter

size has not been shown to have improved efficacy [29].

With recent evidence regarding the safety of conservative

management in PSP, it is imperative to consider standardization

efforts for the vulnerable pediatric population. Standardization

has been shown to decrease hospital LOS, use of CT scans, and

average admission cost without altering rates of recurrence

[9]. In our population, rates of recurrence were higher in the

tube thoracostomy group compared to the group who underwent observation which is consistent with recent literature [15].

Furthermore, ambulatory management is cost-effective when

compared to traditional treatment with tube thoracostomy and

inpatient admission [30]. Standardizing indications for placement of tube thoracostomy and size considerations decreases

associated complications [31]. Further research is needed to

consider needle aspiration as an alternative to tube thoracostomy and failed aspiration as an indicator to proceed to VATS in

the pediatric population [32].

Our study has multiple limitations related to its retrospective single center design, including lack of generalizability. However, given our ED volumes and the 7-year time span covered,

we developed one of the largest case series ever studied [23].

We were limited by the documentation available in the EMR

which prevented reporting factors not reliably charted, such as

chest tube duration, smoking/vaping status, and family history

of pneumothorax. Outside of pneumothorax size, we did not investigate factors associated with conservative versus interventional treatment. Additionally, as this was a retrospective study,

follow-up data was limited to what was available in the EMR at

our institution. While in an ideal situation, the same radiologist

would interpret every CXR, this does not happen in clinical practice and our study reflects normal care delivery.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the significant variation in the management

of pediatric PSP globally and within our institution necessitates

development and implementation of evidence-driven expert

consensus guidelines using quality improvement methodology.

Continued investigation into reliable methods of estimating

pneumothorax size in the pediatric population are necessary.

Declarations

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during

and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the

corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding: This research did not utilize any funding.

Contribution statement: Dr. Touzinsky participated in conceptualization, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of

the data, drafting the manuscript and providing final approval.

Dr. Rymeski, Dr. Hardie, Dr. Crotty and Dr. Vukovic assisted in

conceptualizing this study, revised the manuscript and approved the final version. Dr. Crotty assisted in data analysis, revision of the manuscript and approval of the final version. Dr.

Wilson designed the study, assisted with data collect, analysis

and interpretation, drafted the manuscript and approved the

final version.

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Consent statement: Consent was not required for this work.

References

- J.L. C, Nance ML. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 6th

edition ed. Thoracic Emergencies. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

2010.

- Choudhary AK, Sellars ME, Wallis C, Cohen G, McHugh K. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax in children: the role of CT

in guiding management. Clin Radiol. 2005; 60(4): 508-11. doi:

10.1016/j.crad.2004.12.002

- Chiu CY, Chen TP, Wang CJ, Tsai MH, Wong KS. Factors associated with proceeding to surgical intervention and recurrence of

primary spontaneous pneumothorax in adolescent patients. Eur

J Pediatr. 2014; 173(11): 1483-90.

- Radomsky J, Becker HP, Hartel W. [Pleural porosity in idiopathic

spontaneous pneumothorax]. Pneumologie (Stuttgart, Germany). 1989; 43(5): 250-3.

- Robinson PD, Blackburn C, Babl FE, et al. Management of paediatric spontaneous pneumothorax: a multicentre retrospective

case series. Arch Dis Child. 2015; 100(10): 918-23.

- Shih CH, Yu HW, Tseng YC, Chang YT, Liu CM, Hsu JW. Clinical

manifestations of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in pediatric patients: an analysis of 78 patients. Pediatrics and neonatology. 2011; 52(3): 150-4.

- Park CB, Moon MH, Jeon HW, et al. Does oxygen therapy increase the resolution rate of primary spontaneous pneumothorax? J Thorac Dis. 2017; 9(12): 5239-5243.

- MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Management of spontaneous

pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010; 65 Suppl 2: ii18-31.

- Lawrence AE, Huntington JT, Savoie K, et al. Improving care

through standardized treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax. Journal of pediatric surgery. 6 2020.

- Williams K, Baumann L, Grabowski J, Lautz TB. Current Practice

in the Management of Spontaneous Pneumothorax in Children.

Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques

Part A. 2019; 29(4): 551-556.

- Soccorso G, Anbarasan R, Singh M, Lindley RM, Marven SS,

Parikh DH. Management of large primary spontaneous pneumothorax in children: radiological guidance, surgical intervention

and proposed guideline. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015; 31(12): 1139-44.

- Seguier-Lipszyc E, Elizur A, Klin B, Vaiman M, Lotan G. Management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in children. Clinical pediatrics. 2011; 50(9): 797-802.

- Lee LP, Lai MH, Chiu WK, Leung MW, Liu KK, Chan HB. Management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in Chinese children. Hong Kong Med J. 2010; 16(2): 94-100.

- Kuo HC, Lin YJ, Huang CF, et al. Small-bore pigtail catheters for

the treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in young

adolescents. Emerg Med J. 2013; 30(3): e17.

- Brown SGA, Ball EL, Perrin K, et al. Conservative versus Interventional Treatment for Spontaneous Pneumothorax. N Engl J Med.

2020; 382(5): 405-415.

- Lee JH, Kim R, Park CM. Chest Tube Drainage Versus Conservative Management as the Initial Treatment of Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Journal of clinical medicine. 2020; 9.

- Klassen TP, Hartling L, Craig JC, Offringa M. Children are not just

small adults: the urgent need for high-quality trial evidence in

children. PLoS Med. 2008; 5(8): e172.

- Yoon J, Sivakumar P, O’Kane K, Ahmed L. A need to reconsider

guidelines on management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax? Int J Emerg Med. 2017; 10(1): 9.

- Kelly AM, Druda D. Comparison of size classification of primary

spontaneous pneumothorax by three international guidelines:

a case for international consensus? Respir Med. 2008; 102(12):

1830-2.

- Collins CD, Lopez A, Mathie A, Wood V, Jackson JE, Roddie ME.

Quantification of pneumothorax size on chest radiographs using interpleural distances: regression analysis based on volume

measurements from helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;

165(5): 1127-30.

- Rotondo M, Fildes J, Brasel K, Kortbeek J, Al Turki S, Atkinson

J. ATLS Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors—Student

Course Manual. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons.

2012.

- Mahmood K, Wahidi MM. Straightening out chest tubes: what

size, what type, and when. Clin Chest Med. 2013; 34(1): 63-71.

- Wilson PM, Rymeski B, Xu X, Hardie W. An evidence-based review of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in the adolescent

population. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open. 2021; 2(3): e12449.

- Henderson Y, Henderson Mc. The Absorption Of Gas From Any

Closed Space Within The Body: Particularly In The Production

Of Atelectasis And After Pneumothorax. Archives of Internal

Medicine. 1932; 49(1): 88-93.

- Hill RC, DeCarlo DP, Jr., Hill JF, Beamer KC, Hill ML, Timberlake

GA. Resolution of experimental pneumothorax in rabbits by oxygen therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995; 59(4): 825-7.

- Chadha TS, Cohn MA. Noninvasive treatment of pneumothorax

with oxygen inhalation. Respiration. 1983; 44(2): 147-52.

- Northfield TC. Oxygen therapy for spontaneous pneumothorax.

Br Med J. 1971; 4(5779): 86-8.

- Simpson G, Vincent S, Ferns J. Spontaneous tension pneumothorax: what is it and does it exist? Internal medicine journal.

2012; 42(10): 1157-60.

- Mummadi SR, de Longpre J, Hahn PY. Comparative Effectiveness

of Interventions in Initial Management of Spontaneous Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review and a Bayesian Network Meta-analysis. Annals of emergency medicine. 2020; 76(1): 88-102.

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Landeiro F, Hallifax R, Rahman NM. Cost-effectiveness of ambulatory care management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: an open-label, randomised controlled

trial. Thorax. 2022.

- Tan J, Chen H, He J, Zhao L. Needle Aspiration Versus Closed Thoracostomy in the Treatment of Spontaneous Pneumothorax: A

Meta-analysis. Lung. 2020; 198(2): 333-344.

- Leys CM, Hirschl RB, Kohler JE, et al. Changing the Paradigm for

Management of Pediatric Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax:

A Simple Aspiration Test Predicts Need for Operation. Journal of

pediatric surgery. 2020; 55(1): 169-175.