Introduction

Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus Tract (OCST) is a rare entity

[1-3]. It represents a pathologic channel that initiates in the

oral cavity and opens externally at the cutaneous surface of the

face or neck [4-7]. Generally, this pathology is associated with

longstanding infectious processes [2,4], considered as a common manifestation of pulpal necrosis with periapical pathosis

[1], also, trauma, dental implant complications, salivary gland

lesions, and neoplasms are causes of oral cutaneous fistulas [6].

Despite the fact that this condition is well documented, it still

remains commonly misdiagnosed as it can mimic other disorders such as granulomatous disorder, basal cell and squamous

cell carcinoma, salivary gland and duct fistula, infected cyst, furuncle, or actinomycosis like reported in our case [1,8,3,7].

For successful treatment of odontogenic cutaneous sinus

tracts, the main approach should be to cut off communication

between the infected area and the skin [10]. Usually, this can

be done by non-surgical root canal treatment, but some cases

require surgical-endodontic therapy in order to heal [1,9,7].

The aim of this article is to report a case of odontogenic cutaneous lesion related to left mandibular canine treated with combined surgical and endodontic treatment. It highlights the importance of a well-conducted therapy for the healing of this entity.

Case presentation

A healthy 62-year-old male patient visited the department of

dentistry at “Sahloul University Hospital” in Sousse (Tunisia) for

a cutaneous sinus tract that bothers him aesthetically. The patient reported that one year ago he consulted a dermatologist who prescribed him antibiotics therapy for 2 months without

regression of the lesion. Then, he was referred to a dentist office where he received an endodontic treatment on left mandibular canine, but the lesion didn’t disappear.

Extraoral examination revealed a cutaneous lesion on submental region measuring 2 cm in diameter with depression

aspect, indurated adherent plaque of discharging pus, mucoid

material, and blood (Figure 1a). Clinical intra-oral examination

revealed a poor oral hygiene, moderate fluorosis (Figure 1b).

Tooth 33 was sealed coronary with a temporary filling (Cavit),

asymptomatic, non-tender on percussion, and no deep pockets were present. Transillumination revealed a vertical coronary crack that extends from the cusp to the collar of the tooth

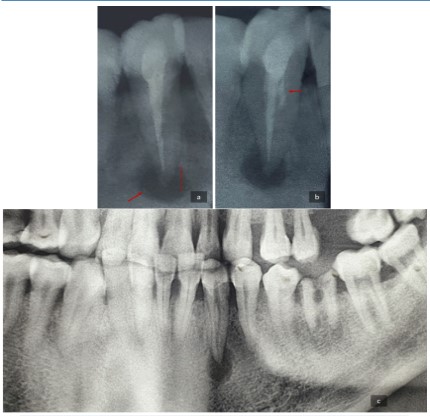

(Figure 1c). The cord-like tissue was not palpable. Intraoral

periapical radiograph revealed a well-circumscribed periapical

radiolucency in relation with tooth 33 and insufficiency in root

canal filling (Figure 2a). Mesial angulation radiograph revealed

a missing second canal that was filled with sealer in its entrance

(about 2 mm) (Figure 2b). The tracing of the sinus tract with

gutta-percha cone wasn’t possible because the orifice of the lesion was closed.

The patient presented an old panoramic radiograph dating

one year before the root canal treatment, and it clearly reveals

the internal morphology of tooth 33 with 2 canals and presence

of the same periapical radiolucency (Figure 2c).

Following these examinations, diagnosis of pulpal necrosis

with chronic peri-radicular periodontitis and extraoral cutaneous sinus tract related to 33 was made. Therefore, endodontic

re-treatment was planned.

During the first visit, following the application of a rubber

dam, removal of temporary coronal filling was done, and access

opening was rectified with endo access bur. The gutta-percha

removal was achieved with retreatment rotary files (ProTaper

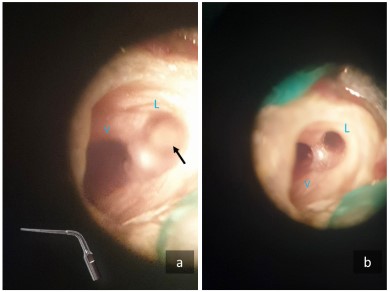

Retreatment Files) without the use of solvents. Then, to free

access to the lingual canal diamond-coated ultrasonic tips were

used for the removal of this hard material under dental operating microscope (Figure 3a). Finally, the two canals were visible and accessible (Figure 3b) and preparation with rotary files

(Fanta Dental Rotary Files) was initiated with abundant irrigation 5.2% sodium hypochlorite. The working length was then

determined (Figure 4) and calcium hydroxide-based medication

mixed with Sodium chloride 0.9% solution was applied. In this

radiography we can see a bone resorption located 3 mm below

the corono-radicular junction.

During the second visit, complete canals preparation was

done, and Ca(oh)2 medication mixed with Sodium chloride 0.9%

solution was reapplied due to serous fluid in the canal. At the

third visit, the cutaneous lesion had different aspect becoming

bigger, productive, budding with yellowish filaments emerging

from its surface, sign of superinfection (Figure 5a,5b). At this

point, the differential diagnosis of Cervicofacial actinomycosis

was evocated and its confirmation required needle aspiration

of the fistula to recover Actinomyces species from an appropriately cultured specimen. The lesion was disinfected and by

seeing closer satellite cysts were visible (Figure 6). The puncture

of the lesion did not extract enough pus or usable blood for microbiological examination so histopathological examination was necessary (Figure 7a) and biopsy of the lesion was scheduled.

Multiple sections of a biopsy specimen from different tissue

levels of the sinus tract were examinated and showed to not

contain Actinomycosis colonies (Figure 7b). Prescription of antibiotics (Penicillin) was needed, root canal filling was postponed

and re-cleaning and shaping of canals and appliance of Ca(oh)2

were required.

At the fourth visit, after three weeks, signs of superinfection disappeared and the cutaneous sinus tract regresses with

no discharge from its surface (Figure 8), thus, root canal filling

was done using single-cone method and bioceramic sealer (Bio-Root™ RCS) (Figure 9).

After one-month, the tooth was clinically asymptomatic, but

no signs of healing were noted, and the fistula didn’t regress.

So, endodontic surgery with fistulectomy was decided to assure

the curettage of the peri-radicular lesion and the excision of the

cutaneous sinus tract.

To access to the lesion, full-thickness flap was reflected, it

revealed a fenestration on the vestibular bone situated in the

peri-apical lesion covered by a granulous lesion. Two bone resorptions recovered by granulation tissue were noted on the

midline between tooth 33 and tooth 32; one was located 3 mm

below the corono-radicular junction like as observed in retroalveolar radiograph and the other was more apical (Figure 10a).

Curettage of granulation tissue was made followed by localized

hemostasis, root-end resection at 3mm level, preparation with

ultrasonic tip (Figure 10b,10c,10d) and finally root-end filling

with Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (Figure 11).

The patient was recalled after 1 week for final restorations.

The coronal track was sealed with flow composite. After 3 months

of the surgery, obvious signs of healing of the cutaneous sinus

tract were observed and the prior depression aspect decreased

leaving a scar measuring 4 mm in diameter (Figure 12). The patient may have to undergo a scar revision for esthetic reasons.

Discussion

An odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract is a pathway through

the alveolar bone which initiates at the apex of the infected

tooth and vacates pus through the face or neck skin [3,4]. It

is commonly considered as consequence of suppurative process of a periapical abscess [1,2]. The sinus tract follows a path

of least resistance and travels through bone and soft tissue

[2,7,11]. Once the cortical plate has been perforated, the sinus tract’s exit point is determined by local factors such as host resistance and anatomic arrangement of neighboring musculature and fasciae, the position of the tooth in the dental arch, the

thickness of the bone and also factors such as gravity and the

virulence of the microorganisms involved can play a role [7,4,5].

In fact, odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts, rather than intra-oral sinus tracts, are likely to occur if the apices of the teeth are

superior to the maxillary muscle attachments or inferior to the

mandibular ones. It was demonstrated that the prevalence of

OCST varies from isolated case reports to 14.7% in large reported series [5] and mandibular teeth are most frequently associated with this pathology [11] like described in this case report.

The successful treatment of cutaneous sinus tract of dental

origin depends on the diagnosis of the source which may be

very challenging because; the patient may not have any apparent dental symptoms; only half of all patients ever recall having had a toothache, the lesion does not always arise in close

proximity to the underlying dental infection and it often have

a clinical appearance similar to other facial lesions, such as osteomyelitis, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma, furuncles,

bacterial infections, congenital fistulas, and pyogenic granulomas [8,4,7].

Clinically the orifice of OCSTs might extend from 1-20 mm

in diameter and may present different shapes, it commonly resembles a furuncle, a cyst, an ulcer, a nodulocystic lesion with

suppuration or it looks like a retracted or sunken skin lesion

[7,12]. If misdiagnosed patients may undergo many inappropriate surgeries and courses of antibiotics before a definitive diagnosis is made and an appropriate therapy are initiated [4].

For the origin of oral cutaneous lesion, the traditional diagnostic approach is an invasive method based on tracing X-ray

after the insertion of a lacrimal probe or sharp-tipped wire into

the orifice opening until resistance is felt. This procedure damages the tissue’s lesion and causes discomfort of the patient and

stress of the operator [11], that’s why authors prefer confirming

the odontogenic origin of the lesion by tracing the sinus tract to

its origin with gutta percha cones [8,7]; in our case we couldn’t

use this technique because the orifice of the cutaneous sinus

tract was closed. Other diagnosis tools are of critical importance such as: Negative pulp vitality testing which indicates the

necrotic causal tooth and palpation of the involved area which

often reveals a cord like track around suspected tooth [8,10],

nevertheless, in most cases the epithelium lining the sinus tract

does not extend deeper from the surface opening and may not

be palpable [2] like in our case. In addition, periapical and panoramic films are essential for diagnosis by showing periapical

radiolucency around the suspected tooth [8]. Some authors showed that CBCT imaging is an effective assistant diagnostic

tool to confirm odontogenic etiology of cutaneous sinus tract;

it reveals periapical radiolucency areas that are not visible upon

panoramic and periapical radiography and cortical plate perforation leading to the lesion [11].

When it’s adequately treated, closure of OCST may occurs

within 5 to 14 days or few weeks [7,11]. Al-Kandari reported

completely healing of the sinus tract after proper root-canal

treatment without surgical treatment in three months leaving a

small scar [8]. In this context, a non-healing lesion could be attributed to a non-odontogenic origin or inappropriate endodontic treatment [11]. In our report, we faced the second situation

where tooth 33 was mistreated a year ago with insufficiency in

filling of the principal canal and missing out the treatment of

the second one.

Above all, it is crucial to know and understand the internal

morphology of root canals for successful non-surgical as well

as surgical endodontic therapy [13]. Over the literature, root

canal morphology and configuration of mandibular canines

have been well documented. Usually, these teeth have single

root and single canal 87% but in 10% of cases, have two canals

join at the root apex and in 3% have completely separated two

canals [14,15]. There are several methods for investigating the

root canal morphology: Cross-sectioning, microscopy, conventional radiography, Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT),

micro-Computed Tomography (micro-CT) and clearing and

staining methods [14,13]. CBCT and micro-CT are the two most

recently introduced investigation methods [13] and researchers

have showed that CBCT is a reliable tool in assessment of root

canal and apical topography in mandibular canines, however it

does not provide images that are as high resolution as those of

micro-CT and its use in accessory canal detection is not recommended [13,14]. In our case, panoramic and retro-alveolar radiography used in different angulations were sufficient to visualize the internal morphology of 33 before starting the treatment.

Based on the classification systems by Briseño-Marroquín and

al, Vertucci, and Weine and al [13], the configuration of our

dental case corresponds to Briseño-Marroquín’s 2-2-1/1 also

known as Vertucci’s II or Weine’s II (2-1). In general, some studies have attributed these variations to the role of genetics, the

importance of ethnic background in tooth morphology and the

difference in age and gender of patients [14].

Due to this unusual morphology, endodontic re-treatment

was challenging especially when detecting the missing canal

and removing the bioceramic sealer in its entrance which could

not be achieved without the use of dental operating microscope and ultrasonic tip. Once canals were accessible cleaning

and shaping were initiated. From a histological point of view,

researchers demonstrated that teeth with chronic apical abscesses and sinus tracts have an overly complex infectious pattern in the apical root canal system and periapical lesion with

a predominance of biofilms [2], for this reason, root-canal irrigation is a critical step on the success of the treatment. Authors showed that conventional chemical debridement with

antimicrobial irrigants, such as sodium hypochlorite (NaoCl) or

chlorhexidine do not always suffice to predictably render root

canals free of bacteria [16]. Recently, endodontics lasers have

been introduced as adjunctive antimicrobial procedures to raise

the success of endodontic treatment and retreatments [1]. In

fact, several studies claim that many biofilms are susceptible

to Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) and 810 nm diode laser [1,16]

and their use in canal disinfection reduced the CFU/ml. These two techniques did not show statistically significant differences

and because of lower side effects, PDT could be the preferred

technique [16].

Additionally, the use of calcium hydroxide as an intracanal

medication is advocated for its benefits; eliminates bacteria that

remain after mechanical debridement due to its high alkalinity

and stimulates bone repair and participates in rapid and successful treatment of sinus tract associated with necrotic teeth

[3,11]. In our case, Ca(Oh)2 was renewed three times due to the

presence of serous fluid in the canals. Every time it was mixed

with saline which, according to authors, limits the dissolution of

calcium hydroxide. Using polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a solvent,

rather than water or saline, can increase the release of hydroxyl

ions enhancing antimicrobial actions, and other improvements

in performance and biocompatibility [17-20].

Between these sessions, the changes in the aspect of the cutaneous sinus tract becoming productive, budding with yellowish filaments emerging from its surface prompted us to make

the differential diagnosis of Actinomycosis. Indeed, this lesion

is characterized by a granulomatous inflammation which form

multiple abscesses connected by sinus tracts that may discharge

with a typical thin, watery characteristic “sulfur granules”

[18,19,21]. These granules are an important diagnostic marker

of Actinomyces species as it contains masses of filamentous

organism. Macroscopically, it resembles yellow grains of sand

(0.1-1 mm in diameter) but can become dark brown due to the

deposition of calcium-phosphate [21]. The diagnosis of this lesion is usually confirmed by culturing the organism, for at least

14 days by needle aspiration of an abcess18. In our case, this

procedure wasn’t feasible so, curettage of the fistula and histological examination was necessary, and the result showed to

be negative. At this point, antibiotics (Amoxicillin and Metronidazole) were prescribed to the patient. Following the American

Association of Endodontists, in cases of odontogenic cutaneous

sinus tracts, antibiotics are indicated to prevent secondary infections and bacteremia in systemically unhealthy cases with

fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, progressive diffuse swelling,

and trismus [10,17,9]. Otherwise, systematic antibiotic therapy

will result in a temporary reduction of the drainage and apparent healing. However, this tract will recur immediately after the

antibiotic therapy is completed unless the initial source is not

eliminated [8,4].

The obturation of root canal system was performed using single-cone method with Bioceramic endodontic sealer (BioRoot™

RCS), it exhibits unique physiochemical properties that can provide exceptional outcomes [3]. In 2021, a novel root canal filling

technique, known as ultrasonic Vibration and thermos-hydrodynamic obturation (VibraTHO) was introduced. It incorporates

indirect ultrasonic sealer activation and short-range warm vertical compaction of a single Gutta percha cone. This technique is

almost as fast and user-friendly as the conventional single-cone

technique and can be a more effective root canal filling method

for anatomically complex root canal systems [22,23].

Studies that reported a high success rate for non-surgical

treatment of teeth with sinus tracts proved that closure of the

tract and periradicular tissue healing may mostly rely on how effectively the clinician controls the intraradicular infection [2]. In

our case, periradicular surgery was decided to remove the granulation tissue and to improve on the result of the treatment.

Indeed, cutaneous sinus tracts are usually lined with granulomatous tissue with a lumen containing a purulent exudate [8].

This pathology usually heals by forming a small pit and hyperpigmentation, which decrease over [9]. Nevertheless, in certain cases surgical removal of the sinus tract extra orally may be

necessary [10] especially when a residual scar persists [11,16]

and it proved to be an adjunct for prompt and speedy management of the lesion [3].

For the Prognosis of this odontogenic sinus tract, it has a

good one after proper treating the offending tooth and surgical

management of the extraoral lesion. Even so, more follow-up

visits are required to confirm the success of our treatment.

Conclusion

This report highlights the importance of correct diagnosis

and therapy in cases of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts.

By enhancing the understanding of this challenging condition,

it is hoped that early recognition and appropriate treatment

approaches can be adopted, leading to improved patient outcomes and enhanced quality of life.

The success of the management of this pathology depends

on proper root canal treatment of the causal tooth which can

be followed by surgical therapy. Beforehand, knowledge of the

internal root canal morphology of the tooth is crucial for the

success of the treatment. Indeed, through this case we showed

that despite its rarity, the presence of extra canals in mandibular canine should be explored before starting the root canal

treatment and its missing will lead to failures.

References

- Mohammad Asnaashari, Sajedeh Ghorbanzadeh, Saranaz Azari-Marhabi, Seyed Masoud Mojahedi Laser Assisted Treatment of

Extra Oral Cutaneous Sinus Tract of Endodontic Origin: A Case

Report J Lasers Med Sci. 2017; 8: S68-S71.

- Domenico Ricucci, Simona Loghin, Lucio S Gonc¸ Isabela N Roc,

Jose F, et al. Siqueira Histobacteriologic Conditions of the Apical Root Canal System and Periapical Tissues in Teeth Associated

with Sinus Tracts J En-dod. 2017; 1-9.

- Karuna Sharma , Ashish Katiyar , Anil Kohli , Sujit Panda. Endodontic and surgical management of odontogenic cutaneous

sinus and mineral trioxide aggregate obturation in a 8 year old

girl: A case report University. J Dent Scie. 2019; 5: 3.

- Ines Kallel, Eya Moussaoui, Islem Kharret, Asma Saad, Nabiha

Douki. Management of cutaneous sinus tract of odontogenic

origin: Eighteen months follow-up. J Conserv Dent. 2021; 24:

223-227.

- Muthu Sendhil Kumaran, Tarun Narang, Sunil Dogra, Sudhir

Bhandari. Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus Tracts: A Clinician’s Dilemma Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020; 11: 440-443.

- Chourouk Chouk. Noureddine Litaiem Oral Cutaneous Fistula

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL) 2022.

- Frederik CURVERS, Petra DE HAES, Paul LAMBRECHTS. Non-Surgical Endodontic Therapy as Treatment of Choice for a Misdiagnosed Recurring Extraoral Sinus Tract. Eur Endod J. 2017; 2: 13.

- Edvard Janev, Enis Redzep. Managing the Cutaneous Sinus Tract

of Dental Origine Open Access Maced. J Med Sci. 2016; 4: 489-492.

- Büşra KOÇ Büşra Melda KENGEL, Esra MAVİ. Surgical treatment

of an extraoral fistula developing due to the left maxillary first

molar tooth of which endodontic treatment was performed and

infection could not be eliminated. Curr Res Dent Sci. 2022; 32:

124-127.

- Duaa Aboalsamh. Non-Surgical Endodontic Treatment of Extra-Oral Cutaneous Sinus Tract: Case Reports. J Oral Health Dent

Res. 2021; 1: 1-4.

- Avi Shemesh, Avi Hadad, Hadas Azizi, Alex Lvovsky, Joe Ben Itzhak, et al. Cone-beam Computed Tomography as a Noninvasive

Assistance Tool for Oral Cutaneous Sinus Tract Diagnosis: A Case

Series. JOE. 2019; 45: 47.

- Yousra Zemmouri, Saliha Chbicheb. Esthetic improvement of a

cutaneous sinus tract of odontogenic origin. PAMJ. 2020; 37.

- Thomas Gerhard Wolf , Andrea Lisa Anderegg, Burak Yilmaz and

Guglielmo Campus, Root Canal Morphology and Configuration

of the Mandibular Canine: A Systematic Review, Int. J. Environ.

Res. Public Health. 2021; 18: 10197.

- Mandana Naseri , Zohreh Ahangari , Nastaran Bagheri , Sanaa

Jabbari, Atefeh Gohari. Comparative Accuracy of Cone-Beam

Computed Tomography and Clearing Technique in Studying Root

Canal and Apical Morphology of Mandibular Canines, IEJ Iranian

Endodontic Journal. 2019; 14: 271-277.

- Mazen Doumani, Adnan Habib, Maram A Alhenaky, Khaled SH

Alotaibi, Maali S, et al. Root canal treatment of mandibular canine with two root canals: A case report series, Journal of Family

Medicine and Primary Care. 2019; 8.

- Mohammad Asnaashari, Mostafa Godiny, Saranaz Azari-Marhabi, Fahimeh Sadat Tabatabaei, Maryam Barati. Comparison

of the Antibacterial Effect of 810 nm Diode Laser and Photodynamic Therapy in Reducing the Microbial Flora of Root Canal in

Endodontic Retreatment in Patients With Periradicular Lesions,

J Lasers Med Sci. 2016; 7: 99-104.

- American Association of Endodontists, Guide to Clinical Endodontics Sixth Edition.

- Abdu A Sharkawy, FRCPC Anthony W Chow. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. 2022.

- Saurabh Sunil Simre, Anendd A. Jadhav, Chirag S. Patil. Actinomycotic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible - A Rare Case Report. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery. 2020; 10.

- Basil Athanassiadis and Laurence J. Walsh. Aspects of Solvent

Chemistry for Calcium Hydroxide Medicaments, Materials.

2017; 10: 1219.

- Márió Gajdács, Edit Urbán, Gabriella Terhes. Microbiological

and Clinical Aspects of Cervicofacial Actinomyces Infections: An

Overview. Dent. J. 2019; 7: 85.

- Yong-Sik Cho, Youngjun Kwak, Su-Jung Shin. Comparison of Root

Filling Quality of Two Types of Single Cone-Based Canal Filling

Methods in Complex Root Canal Anatomies: The Ultrasonic Vibration and Thermo-Hydrodynamic Obturation versus Single-Cone Technique Materials. 2021; 14: 6036.

- YS Cho. Ultrasonic vibration and thermo-hydrodynamic technique for filling root canals: Technical overview and a case series. Int Endod J. 2021; 54: 1668-1676.