Introduction

A fracture of the pars interarticularis of C2 causes traumatic

spondylolisthesis at C2-3 and is referred to as the Hangman’s

fracture. The Hangman’s fracture classically results from hyperextension and distraction of the upper cervical spine, causing

the axis to break symmetrically across its pedicles or lateral

masses, and may involve the body of the vertebrae. The most

common causes of this fracture are falls and car accidents [1-3]. Cervical spine injury associated with backward tilting of

the trunk cabin is rare and has not yet been reported in the

literature. This trauma can be fatal due to severe major organ

damage. We present a case of type II Hangman’s fracture in a

64-year-old man that resulted from trauma to the neck when

it was caught between a truck cabin tilting backward and the

base frame.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old male truck driver tilted the truck cabin forward

to check the engine (Figure 1). After checking the engine, he

tilted the cabin backward. However, he forgot that he had put

his head in the engine room, and his neck was caught between

the truck cabin tilting backward and the base frame. Fortunately, he was freed from the cabin by applying traction to his body.

He was admitted to the emergency department of our hospital

with neck pain and limited range of movement due to pain. In

the field, emergency services had ensured complete spinal immobilization by using cervical collars.

On physical examination, the patient was neurologically intact and showed moderate to sharp midline tenderness in the

cervical spine and paraspinal muscles. No signs of intracranial

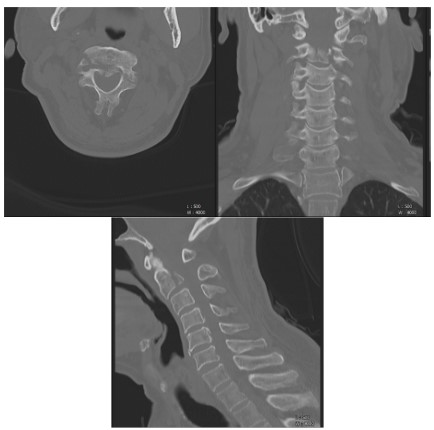

involvement were observed. Plain radiography, three-dimensional Computed Tomography (CT), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine were performed. No bony

abnormalities were found in the open-mouth view; however,

a fracture of the C2 pars interarticularis with angulation and

translation of C2-C3 was found in the lateral view (Figure 2). A

three-dimensional CT scan revealed fractures of the axis body

and both pars interarticularis of the axis, with angulation and

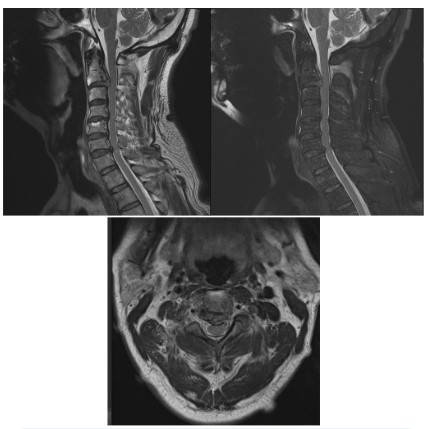

translation of C2-C3 (Figure 3). MRI did not show signal change

in the spinal cord but showed intervertebral disc protrusion between C2-C3 in the T2 weighted image (Figure 3).

We diagnosed the patient with traumatic spondylolisthesis of the second cervical Levine-Edwards type 2 (Hangman’s

fracture). We initially considered conservative treatment, and

halter traction was applied with 6 pounds of weight. We subsequently reduced the halter traction by 6 pounds to 2 pounds

and confirmed that the reduction was well-maintained. We

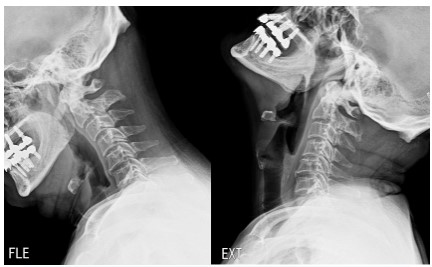

then applied traction and a halo vest using fluoroscopy (Figure 5). After checking the reduced angulation and translation of C2-3, the patient was discharged after 5 days. Three months later,

radiographs and cervical CT scans showed union of the C2 fracture (body and pars interarticularis), and the halo vest was removed (Figure 6). No complications were observed. The patient

reported no neck pain or discomfort at the last follow-up visit.

Discussion

The cabin of a truck is the inside of the truck, where the

driver is seated. Cabover trucks refer to trucks with a body style

or design in which the cabin is positioned directly above the engine and front axle. The entire cabin is tilted forward to access

the engine. Accidents related to backward tilting of the cabin

are rare but can be fatal due to severe major organ damage.

Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis, also known as the

Hangman’s fracture, is the second most common fracture pattern of the C2 vertebrae after odontoid fracture [1]. Schneider

first noted this fracture in 1965 [2]. The injury involves bilateral

fractures of the ring of the axis through the pars interarticularis

of C2. Thus, during the injury, the forces across the C2 and C3

vertebral bodies widen the spinal canal, although a low rate of

neurological deficits has been reported [3]. High-speed motor

vehicles or fall accidents typically account for this type of injury,

and the most common mechanism involves hyperextension

with axial loading or distraction and rebound hyperflexion [4].

A violent hyperextension force stretches the anterior structures

and compresses the posterior structures, causing them to tear

apart, resulting in a pars interarticularis fracture. Continuation

of this force causes the anterior longitudinal ligament and anterior disc to be torn. If the force continues for an extended time,

the disc is separated from C3, and there is a C2–C3 dislocation.

Type II fractures are thought to be caused by a combination of

extension and axial loading, followed by flexion and compression loads [5]. Many type II fractures are stable; thus, if stability

is proven, they can be treated with nonsurgical management

via a rigid cervical collar or halo vest [6,7].

At the time of the accident, the patient’s neck was between

the truck cabin, which was tilted backward, and the base frame

without hyperextension or distraction. We thought that the

only mechanism of trauma was a direct blow to the cervical

spine and not the common mechanism of Hangman’s fracture.

However, this patient had Hangman's fracture type II and C2

body fractures without any neurological deficits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, an injury related to a truck cabin tilting backward can cause damage similar to that observed in judicial

hanging, with traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. Primary

care physicians should be aware of the possibility of axis fractures in patients with a history of truck cabin tilting backward-related injuries. This case suggests that in patients with Hangman's fracture type II and C2 body fractures, non-operative

management with a halo vest is a safe and efficacious option.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: None.

Funding sources: The author(s) received no financial support

for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Editage (www.

editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

References

- Hadley MN, Dickman CA, Browner CM, Sonntag VK. Acute axis

fractures: A review of 229 cases. J Neurosurg, 1989; 71: 642-647.

- Schneider RC, Livingston KE, Cave AJ, Hamilton G. “Hangman’s

Fracture” of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg, 1965; 22: 141-154.

- Effendi B, Roy D, Cornish B, Dussault RG, Laurin CA. Fractures of

the ring of the axis. A classification based on the analysis of 131

cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981; 63-B: 319-327.

- Francis WR, Fielding JW, Hawkins RJ, Pepin J, Hensinger R, Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;

63-B: 313-318.

- Joel T, Adam K, Nicholas TS, John CF, Brandon DL. Hangman’s

Fracture. Clin Spine Surg. 2020; 33: 345-354.

- Rouzbeh ML, Homa S. C2 Body Fracture: Report of Cases Managed Conservatively by Philadelphia Collar. Asian Spine J. 2016;

10: 920-924.

- Schleicher P, Scholz M, Pingel A, Kandziora F. Traumatic Spondylolisthesis of the Axis Vertebra in Adults. Glob Spine J. 2015; 5:

346-357.