Introduction

Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibromas (ENA) involving paranasal sinuses represent an unusual finding and the localization at

the level of frontal sinus is an extremely rare event with few

cases reported in literature [1,2]. The clinical presentation is aspecific, lacking the typical features of their more common nasopharyngeal counterpart with which they share the histological

characteristics.

We present our experience in the diagnosis and management of a massive frontoethmoidal angiofibroma, treated with

a combined endoscopic transnasal and Osteoplastic Flap (OPF)

approach.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old man was referred to our department for a

nine-month history of bilateral nasal respiratory obstruction

and right epistaxis.

The endoscopic endonasal evaluation revealed a pinkish,

firm, capsulated mass of apparent vascular nature, completely

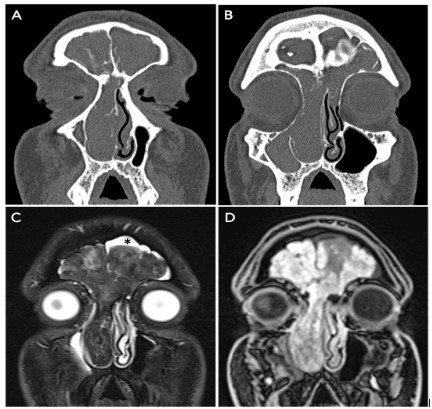

obstructing the right nasal fossa. A CT scan, as first line radiological investigation, revealed an expansive mass occupying the

right nasal fossa, with opacification of the ipsilateral antrum

and both frontal sinuses, thinning of bony septa of the anterior

ethmoidal complex as well as remodeling of interfrontal septum

and frontal beak. An MRI with gadolinium showed an inhomogeneous neoformation both on T2-weighted and enhanced T1-weighted sequences, involving the right ethmoid and bilateral frontal sinuses (Figure 1). A biopsy of the mass was performed

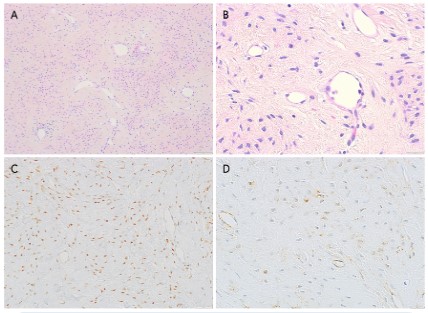

under local anesthesia. Histopathological examination revealed

fibrocollagenous stromal proliferation with an admixture of

variably sized and angulated vascular spaces.

Immunohistochemistry showed that endothelial cells were

reactive with endothelial cell markers (e.g., CD31, CD34, others). Smooth muscle actin-positive cells were found around the

circumference of the vascular spaces. Spindle-shaped and stellate stromal cells were positive for nuclear androgen receptor,

nuclear β-catenin and vimentin, whilst negative for S100 protein, estrogen and progesterone receptor (Figure 2). The histology and immunohistochemistry were compatible with juvenile

angiofibroma. The patient was then scheduled for a combined endoscopic endonasal and OPF approach. The portion of the

lesion obstructing the right nasal cavity and involving the anterior ethmoid was removed trans-nasally. The lesion appeared

to originate from the frontal beak, which was accurately drilled

out after a right frontal sinusotomy type IIB sec. Draf was performed. An ethmoidectomy, middle antrostomy and sphenoidotomy were performed without evidence of involvement by the

lesion. The OPF approach allowed complete removal of the lesion occupying both frontal sinuses, and the bony walls’ surface

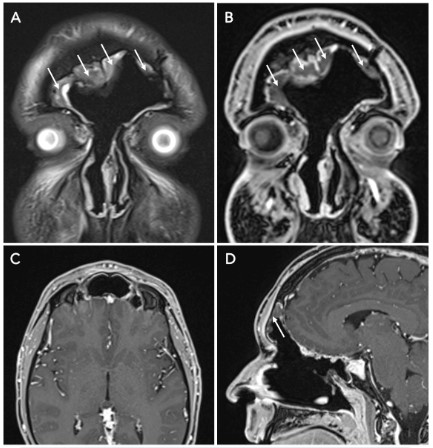

was drilled out, in order to eliminate possible microscopic remnants. An MRI performed 48 hours after surgery excluded any

persistence or postoperative sequelae. Postoperative course

was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 72 hours after

surgery. The follow-up was performed with nasal endoscopy at

1, 3, 6, 12 months for the first year after surgery and then two

times per year, combined with MRI performed every 6 months;

2 years after surgery no recurrence was observed (Figure 3).

Discussion

ENA is a rare entity, with less than 200 cases reported in

medical literature. Although the histologic features are the

same of much more common Juvenile Angiofibroma (JA), the

clinical appearance differs significantly; therefore, they are considered as two different entities by many authors. In contrast

with JA, which has a characteristic localization, due to its precise

site of origin at the level of pterygoid, ENA could involve any site

of the upper aerodigestive tract, but nasal septum appeared to

be involved in the majority of cases. Windfur et al. in their large

literature revision of 174 cases of ENA did not report any case

of frontal sinus involvement, which appears to be an unusual

site of presentation for this pathology with few cases reported in current literature [3]. The age of presentation is typically

around the second and third decade of life. In contrast with JA,

the occurrence in females is not unprecedented (M:F 2:1). The

main symptom is nasal obstruction, either in combination with

epistaxis (25.8%) or other symptoms (12.6%). Diagnosis of JA

is confirmed by imaging due to the characteristic radiological

features; this is not possible when dealing with ENA. Considering the aspecific presentation of ENA, the clinical diagnosis

of this pathologic entity is not straight forward, and differential

diagnosis includes the majority of sinonasal vascular benign tumors and low-grade malignant tumors. In presence of lesions

compatible with JA, biopsy is strongly contraindicated to avoid

bleeding which could be difficult to deal with; fortunately, the

reduced vascular component of ENA compared to JA, makes biopsy a feasible procedure with a low risk of massive bleeding.

Histologic findings and immunohistochemistry play an essential

role in differentiating angiofibromas from other vascular malformations or tumors (e.g. lobular capillary hemangioma, sinonasal polyps, peripheral nerve sheath tumors, solitary fibrous tumor and desmoid tumor) [4,5]. Complete surgical resection is

considered the best treatment option. The reduced vascularization of ENA compared to JA accounts for limited intraoperative

bleeding, making preoperative embolization of the mass unnecessary in the majority of cases. Nowadays, the majority of

sinonasal benign and malignant tumors may be treated with

an exclusive endoscopic approach, with recurrence and complication rates similar to that reported for external approaches.

In the present case, the choice of a combined endoscopic endonasal and external approach via an OPF, was based on the

massive involvement of well pneumatized frontal sinuses by the

lesion. Kim et al. reported a case of frontal sinus ENA treated

with transnasal approach and frontal sinus trephination which

did not allow a complete excision of the lesion [6]; to gain a

complete exposition of the sinus and easily reach radicality, we

chose to perform an OPF approach.

Conclusion

The localization of angiofibromas at the level of frontal sinus

is extremely rare, however they must be taken into account in

differential diagnosis of frontal sinus neoformations. A biopsy is

necessary for the diagnosis and it’s a safe procedure, with massive bleeding being a rare occurrence.

A combined endoscopic endonasal and osteoplastic flap approach provides a safe and effective treatment of these lesion

when a massive involvement of the frontal sinus is present,

overcoming the limits of the single-approach procedures.

References

- Kurien R, Mehan R, Varghese L, Telugu RB, Thomas M, et al.

Frontoethmoidal Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma With Orbital Pyocele. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020; 145561320972600.

- Rao MS, Lakshmi CR, Sonylal PE, Chakravarthy VK, Murthy PS.

Recurrent angiofibroma of ethmoid region - a rare variant. J Clin

Diagn Res. 2014; 8: KD01-2.

- Windfuhr JP, Vent J. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma revisited. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018; 43: 199-222.

- Perić A, Sotirović J, Cerović S, Zivić L. Immunohistochemistry

in diagnosis of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma originating

from nasal cavity: case presentation and review of the literature.

Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2013; 56: 133-141.

- Lester D.R. Thompson, Justin A. Bishop. Head and Neck Pathology. 2016.

- Kim JS, Kwon SH, Kim JS, Jung JY, Heo SJ. Extranasopharyngeal

Angiofibroma of the Frontal Sinus. J Craniofac Surg. 2019; 30:

e432-e433.